Making 20,000 count

Deloitte has published its latest annual Policing 4.0 report into the state of policing, making a number of recommendations as to how forces and government can take advantage of the recent uplift and address the consequences of ‘unpalatable’ decisions leaders had to take to reduce budgets over the last decade.

Despite the difficult position forces found themselves as a result of a fall of 16 per cent in funding, Policing 4.0: How 20,000 officers can transform UK policing highlights the progress that has been made, even though demands from the public increased in several areas.

Drawing on significant research conducted between July and September 2019, Deloitte’s report provides a number of tools and frameworks to support the difficult decisions on police priorities and highlights where new capabilities need to be developed. It also provides examples of interesting and/or proven approaches from across UK forces and other sectors.

As well as surveying chief officers, police and crime commissioners (PCCs) and experts, the report looks at wider trends in society and other sectors.

Technology remains the most significant driver of change in policing, with an arms race between offender and law enforcement accelerating over time.

Deloitte’s Tech Trends 2019 highlighted how digital reality, cognitive technologies, and blockchain are growing rapidly in importance. These three trends are poised to become as familiar and impactful as cloud, analytics and digital experience are today.

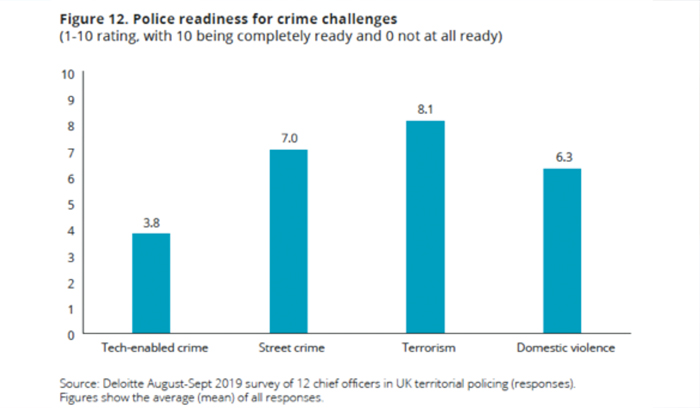

The survey of police readiness for key crime challenges revealed that leaders feel less well prepared to reduce the harms of online and private sphere crimes than traditional street crime and terrorism (see diagram).

Police leaders were most concerned about their capacity to deal with technology-enabled crime, with interviews showing that these concerns related to:

- challenges in building technological tools and acquiring (and retaining) staff with these in-demand skills;

- difficulties in responding to boundaryless crimes within the geographically based police structures that currently exist;

- a recognition that policing’s capability in these areas is already lagging, in part due to the relatively low political importance that has been attached to tackling those crimes that are most often digitally enabled (such as fraud);

- the growing proportion of offences where technology is a critical enabler in committing crimes or evading detection;

- limited force-level ability to influence and regulate the online environment given the increasing power of global internet platforms not domiciled in the UK; and

- major problems dealing with existing volumes of digital evidence, let alone the increased volumes growing each year.

“UK policing performance stood up surprisingly well for many years but the pressures eventually told,” the report authors explain. “After a spike in serious violence since 2015, crime is now the third highest public concern in England and Wales after Brexit and healthcare. Police visibility in England and Wales has fallen. And chief officers we spoke to reported that they had to make increasingly unpalatable decisions on which crimes could be given a full investigative response.

“The UK Government has now responded decisively, however. After small funding injections targeted at reducing serious violence in early 2019, the Chancellor’s September ‘spending round’ promised an additional £750 million investment in English and Welsh policing in 2020.

Further increases have been promised in future years as the Government aims to deliver on the ambitious target to recruit 20,000 more officers over the next three years as well as invest in the wider justice system.”

This injection of funding has made police leaders optimistic, they add. Funding may now recover to 2009 levels by 2022 and leaders are confident that they have enhanced the efficiency of their organisations during the period of austerity. Yet there is some caution too. The proposed funding increase would still mean that officer numbers in England and Wales remain nine per cent lower in per capita terms than ten years ago, given population growth.

There is also uncertainty over future policy decisions nationally, the impact of Brexit and a shift in local political leadership as around half of PCCs will be replaced after the May 2020 elections – approximately one third are not seeking re-election.

“These uncertainties reflect the fact that policing has reached a new inflection point,” the authors suggest. “The policy and fiscal framework in England and Wales that was ushered in by the then Home Secretary, Theresa May, in 2010 and which held firm until she stepped down as prime minister in 2019 is now over. Decisions by politicians and police leaders over the coming months in England and Wales – and parallel decisions in Scotland and Northern Ireland – will shape a new settlement and determine the effectiveness of UK policing for years to come.

“There is now a vital opportunity to address historic challenges and prepare for the future. The trends of accelerating technological and societal change highlighted in this report have already created an environment that is very different to ten years ago – and there are gaps emerging in policing’s ability to cope with change. None of the leaders we surveyed felt policing was yet well prepared for tackling technology-enabled crime. There were also major concerns about policing’s capacity to use technology effectively. And there were concerns about policing’s capacity to deliver a coordinated national, regional and local response to emerging threats.”

Recommendations for UK Government and the National Policing Board

Policing must be as clear as possible about its mission, aspirations and priorities and national investments must be guided by a clear view of what the public values and needs.

- Continue to invest beyond the levels required to hire the additional 20,000 officers in England and Wales and rebuild service strength in Northern Ireland. This includes an appropriate balancing investment in: Training and equipment (including technological enablement); Functions that are essential to policing effectiveness but don’t always require warranted officers (eg, forensics and intelligence); and Downstream costs in the criminal justice system, and upstream preventative work.

- If the above is not possible due to changes in priorities or fiscal position, adjust timescales for increasing officer numbers. Under-investing in the right support staff, technical specialists and technology will result in policing being less productive and could drive some forces to reallocate frontline officers into less operational roles.

- Build new crime reduction capabilities that logically sit above the level of individual forces. There is currently a gap in national capabilities for preventing high-volume, less serious crimes, particularly online crime (most notably fraud) and traditional acquisitive crime. Local police forces lack many of the levers necessary for effective crime prevention (for example, engaging with industry on product security standards or liaising with banks to tackle illicit finance). The National Crime Agency, meanwhile, is oriented towards individual serious cases and organised threats, rather than cumulative system-wide crime harms – so as a result cannot easily prioritise building the capabilities to prevent high-volume, lower seriousness crime. Opportunities are missed to prevent victimisation and to tackle serious violence and other government priorities.

- Provide increased stability of investment and stronger coordination around national technology-enabled transformation and specialist capability programmes. Funding for critical programmes is still not provided on a multi-year basis, and this is slowing down the delivery of benefits to officers and staff. The multiplicity of governance arrangements for national programmes is also creating duplication of effort and increased workload for police forces. It seems inevitable that at some point an organisation will need to be assigned to house these ongoing long-term programmes and the capabilities needed to support them.

- Harness the Police Foundation Policing Review, announced in September 2019, to build solutions and consensus around overall police structures and governance. Our research showed clear dysfunction in the governance of national and regional capabilities and critical programmes. This report raises some options for improvement but any solution involves trade-offs and will be contentious.

Recommendations for local policing, including devolved administrations

The report identifies four actions that can support local policing:

- Develop ‘digital twins’ of your organisation to develop more insight on where to invest new resources. This can build on progress made in understanding demands on policing for Force Management Statements and will help organisations to anticipate and unblock organisational bottlenecks and capability gaps.

- Refuse to compromise on quality or diversity in the upcoming recruitment drive, even if it means a delay in hitting targets. With some 50,000 new recruits required to meet officer number targets, entrants over the next few years will be the backbone of the service for decades.

- Build on collective work relating to digital policing. Contrary to the overall perception, several police forces in the UK and internationally are making huge strides towards becoming data-driven organisations, deploying advanced analytics and intelligent automation solutions ethically, embracing new national capabilities and managing ICT infrastructure efficiently and securely.

- Anticipate and avoid ‘change overload’. Policing has delivered major changes but there is more to come. At a time when police HR, change and communications teams are already stretched by locally-led programmes, a set of national programmes (for recruitment, training and technology) are being implemented. They all offer potential productivity gains but also require new training and communications drives that will need to be carefully managed and sequenced to ensure the workforce is not confused and overwhelmed by changes.

The report says all the recommendations directly support or complement the delivery of the Government’s manifesto commitments on crime and policing. Some will simply require ongoing focus but others require new decisions or programmes of work nationally or locally.

“All recommendations are, of course, intended to support the development of the next evolution of UK policing, Policing 4.0,” it adds.

“Policing 4.0 is about building an ecosystem that harnesses clear thinking, data, person-centred design and cyber-physical systems to improve public safety and create public value. We believe that this year’s changes in policing context provide an unparalleled opportunity to make Policing 4.0 a reality.

“If these gaps are addressed, and policing avoids the temptation simply to rebuild the policing model of ten years ago, the prize is vast. We propose nine measures that could collectively help ensure that the addition of 20,000 officers transforms policing effectiveness today and in future.”