App-lying engagement

The use of smart technology to involve communities in crime reduction makes complete sense, but its introduction has not been without controversy. However, new applications are beginning to emerge and make it easier to connect with the public.

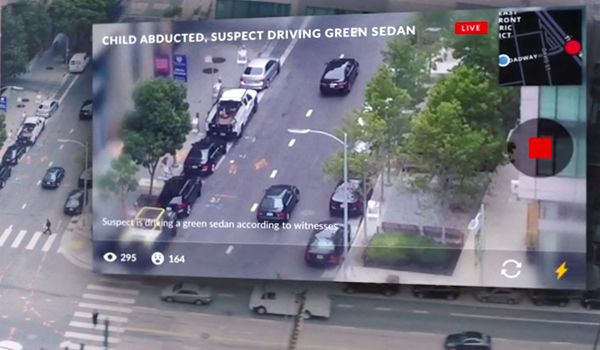

In the latest promotional video for the Citizen smartphone app, the San Francisco Police Department receives a report of a four-year-old child being abducted by an unknown suspect driving a green vehicle. As details of the crime-in-progress are broadcast to patrol cars in the area, employees at Citizen headquarters are listening in and send out instant, real-time alerts to the apps subscribers across the city. Users in coffee shops, office blocks or walking along the streets pick up the alerts and within moments, several are live-streaming video of the suspect vehicle, allowing Citizen to send out a stream of updates on its location. The vehicle is eventually filmed making its way down a quiet side street allowing the police to narrow down its location. The video ends with police officers arriving at the address and the final shot is of the abducted child being carried out of the house by an officer to be reunited with his parents. At that moment a voiceover asks: What will be possible when technology unites the forces of good? Citizen began life as an app called Vigilante, which was pulled from the Apple app store less than a week after its release in November 2016 over fears that it was encouraging members of the public to take the law into their own hands. The concern was that Vigilante actively encouraged users to get involved when they received a crime report, suggesting that average and ordinary citizens should approach crimes in action as a group to see if they could intervene. There were also concerns about users of the app confronting dangerous criminals, or intimidating and harassing innocent people in an area where a crime had been reported because they matched an image of what they believed the suspect should look like. The app re-launched in March 2017 under the name Citizen without the crime-reporting feature. However, as the promotional film clearly shows, users can still message each other and record videos of incidents on their phones and livestream them through the app. Originally launched in New York, where the service reportedly has 120,000 active users, it began operating in San Francisco late last year and has proved popular enough to enable the company to secure an additional $12 million in funding from its investors. The need has never been greater for technology that informs and protects the public, said Citzen in a statement that marked the launch. We created Citizen to drive down crime and increase accountability. When everybody does their part, Citizen is a tool that could save your life. It is not the first time smartphone technology has been used in this way. The PanicGuard app, backed by the charity Crimestoppers, was launched in the UK in 2012. It allows those who believe they are in danger, such as being threatened on a date, or being followed, to send out an alert to an alarm-receiving centre simply by shaking their phone. The centre then attempts to call the user back. If no reply is received after three rings, the police are called and given details of the users location. At this point, the app also activates video and sound recording on the device, allowing staff at the centre to see and assess the situation for themselves. One woman who used the service after she was stalked by her husband provided a testimonial in which she said: Thanks to the video evidence, I managed to prove I was being harassed and got a restraining order. According to Crimestoppers, PanicGuard acts as a security blanket to make users feel safe when travelling alone or finding themselves in uncomfortable situations. However, the latest generation of crime reporting apps have the potential to dramatically change the very nature of community policing the relationship between the police and the public. Citizen is able to operate without any official cooperation from either the New York or San Francisco police departments because, unlike in most other countries, the emergency services broadcast using unencrypted radio signals, which can easily be intercept