Culture of silence

A lack of emotional support within the police is leading to increased rates of PTSD and burnout says Sarah-Jane Lennie.

When you are a police officer, your emotions have to be hidden or pushed down. Officers work hard to detach themselves from their emotions as a way to cope in a culture that has an expectation of silence in the face of trauma. This culture directly contributes to the increase in mental health issues in police officers and staff.

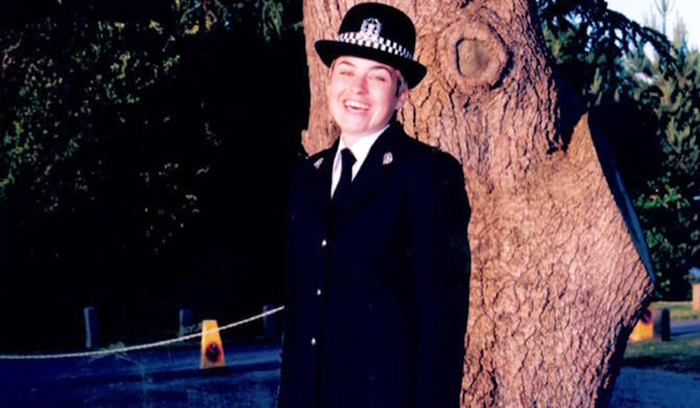

I should know. Policing is in my blood. I was a police officer for 18 years. I am a child of two police officers and my husband is a police officer. My dream was to become a detective chief inspector, running murder inquiries. I made it to detective inspector. But then my world – and my mental health – came crashing down around me.

I found that I was constantly reliving my investigations in intense detail. I was reviewing every death, every shooting, every kidnapping that I had investigated. Over and over, and over. I was terrified. I didn’t sleep because I was flooded with adrenalin and a physically crushing anxiety. That adrenaline coursing through my body had me on high alert 24/7 and I saw risk and danger everywhere I looked.

I struggled to leave work as there was always more that I could do, more that could be done to protect others and reduce the risk. But my mind was fragmenting as my brain tried to cope with all of the detail I was scrutinising in an attempt to keep myself and everyone else safe.

When I was home I was not present because I was reliving the nightmares of the day. There wasn’t a single moment as a police officer that I experienced any respite from that fear. Finally, I had to make a choice: my mental health or my career. It broke my heart to step away from the job I loved. I kept my sanity, but the dream was over.

I did not let my investigative skills go to waste and I turned to academia to see if I could find out what the deep rooted problem was at the heart of policing. My doctorate examined the emotional culture of the police in England and Wales and its contribution to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in officers. I am now a chartered psychologist and academic researcher. I have been working to capture the emotional lives of police officers, to reveal how much pressure they are under to hide their true feelings and the ultimate consequences this has on their mental health.

At a time when police officers are also having to deal with public anger, I believe it is worth thinking about the challenges they face as individuals on a daily basis and how that affects the kind of police service the public gets.

This ‘emotional silencing’ was something I experienced as a serving officer and my subsequent study revealed I was not alone. What is far more troubling is that this emotionally stifling environment is directly contributing to PTSD in police officers, as it forces officers to dissociate from their emotions – a key contributor to PTSD.

I wanted to give police officers a voice and highlight the role of police service when it comes to the mental health of their officers and staff. I used audio diaries to capture stories from individual officers so I could assess the factors which were contributing to increasing levels of mental ill-health within the police service.

The diaries allowed officers to speak frankly about their emotional experiences and speak up on issues which they felt were unjust. They recorded their diaries on a smartphone app, following a prompt sheet. Participants could talk about whatever they wanted to, but the prompt sheet reminded them to describe how they felt, if they could express this emotion to anyone and if they displayed an emotion contrary to the one they experienced. These are stories that would otherwise have gone untold or unheard.

I spoke to officers from 16 different forces who provided me with over 25 hours of material in 137 diary entries. The sample group was composed of 11 uniformed constables, three detective constables, seven uniformed sergeants, three detective sergeants and three detective inspectors. They came from a range of specialist units including offender management, counter terrorism, tactical, firearms, CID, sexual offences, major investigations and roads policing.

The volunteers who bravely agreed to take part discussed experiences and feelings that they had never spoken of before. Some of the incidents they talked about occurred many years ago, but were clearly still at the front of their minds. Together, they revealed a culture of silence and stigma around emotional expression within the UK’s police forces.

Emotional suppression is the rule

A major theme emerged from these diaries: emotions are seen as a weakness and an indicator of incompetence, operating as unofficial performance measures. If you are caught displaying an emotional reaction, then you are considered unreliable and unfit for the job. Emotional suppression is the rule. This was communicated through training, policy and procedure and by observing colleagues and the behaviour of senior leaders.

Officers said that these ‘feeling rules’ (unwritten standards that govern emotional experience and response) are enforced through career limiting sanctions where officers are removed from their team, post or specialism as they are perceived as presenting a risk to the organisation. In particular, fear cannot be expressed. One detective constable told me: “I don’t think that you can be openly emotional as an officer, you might be seen as a bit of a wimp.”

This feeling rule appears to apply to most areas within an officer’s life, whether it be with colleagues, supervisors, back at the station or with family.

A female child protection officer described how emotions were something she hoped to deal with at some later point – after the job was done. She said:

I think that compartmentalising and squashing down of your immediate reaction is a kind of unwritten rule as a police officer, it is certainly one practice that I have adopted to deal with traumatic incidents […] because you have got to perform.

She went on to say that everyone finds their own way. Some “squash it down”, some do not acknowledge it and are perhaps not aware of how they are feeling until later. She said this was the case for her. She would tell herself not to panic, take a breath and carry on with her job. “I would just cry later”, she said.

Officers felt that they were considered to be emotionally different to other members of the public and that they should not be affected in the same way by traumatic events. One male detective said: “You are a cop and you deal with this kind of thing, day in and day out, and you should just crack on.”

This encourages officers to dissociate, suppress or detach themselves from their emotions. There is a lot of crying in patrol cars away from the eyes of the public, or colleagues. One female response sergeant told me about how she had to deal with a sudden death of an elderly male, shortly after the death of her own mother. She got back into her patrol car and drove off, before stopping to “choke back the tears” and somehow managing to keep them in check. She added: “You do what you have to do, you go out to the car… I sit there at times and think, ‘oh dear lord’. And then the radio goes and you are off on your next job again. So you file that away and you get on with it…”

Although police forces do have certain health and wellbeing procedures in place, the reality on the ground is that officers feel abandoned. Perhaps one of the most shocking things, according to my participants, is the lack of specialist mental health awareness training or proper counselling to help officers deal with their emotions. This lack of support is something that the officers I spoke to struggled with.

One detective sergeant lamented the waiting times for in house occupational support, and felt he was “fobbed” off by supervisors when directed to the Employee Assistance Programme (also known as CIC – Confidential Care). He said: “They just go “ring CIC” but it takes me six weeks to get to see someone, I can’t go to occy health because there isn’t any spots, and I have got to go through an assessment process.”

The counselling services most forces do provide are essentially the same as for any organisation, which is an outsourced Employee Assistance Programme of six sessions of cognitive behaviour therapy (or CBT). Clearly, for such a highly stressed profession, this is not adequate.

Robots, fear and danger

Society expects police officers to behave in certain ways and that is informed by the representation of police in the media. This expectation bleeds into every area of a police officer’s life – it can even inform the expectations of family and friends. Some of my volunteers told me how they were expected to be more able to cope with deaths or tragedies in their families.

They told me how friends expected them to provide protection and guidance in social settings. If there was a fight in a bar, or someone was becoming aggressive in public, friends and family would look to the police officer to step in.

This was an important point for me to explore. It led me to understand how isolated officers are. There is no space in their lives to process their experiences.

One response officer said that this had led them to be viewed as subhuman, or robotic. She said: “You are expected to be the robot that comes in and deals with horrific incidents and supports the family and supports whoever is involved, picks up the pieces and goes away again.”

One female offender management officer told a revealing story about fear and danger. She was working an evening shift and visiting a registered sex offender. She was alone with no support and the visit did not go well. The woman found herself in the house of a convicted criminal who was becoming increasingly aggressive and threatening.

She said: “I thought that I was going to get my head kicked in when I came out of there I was physically shaking […] I had nobody, there was nobody on our division in our unit, there was no supervision.”

The officer ended up having to draw her CS gas to control the man. But this leads to another issue: the worry over procedure and complaints. These are the dual threats in an officer’s working life: are they going to be assaulted and are they going to be investigated for protecting themselves?

That last question is a particular concern for firearms officers who are constantly operating in high risk, high stress situations. The public may think, then, that a massive amount of resources are put into maintaining their mental health. But while firearms officers are made aware of the need to be “mentally healthy” by their force as part of their training, this does not lead to a greater openness and support within the firearms units. According to the officers I spoke to, there is instead a higher expectation of emotional regulation.

One officer said that “there is always the fear that if you say anything [emotional] then they will pull your ticket” and “that could put your future in jeopardy”. They said it would be beneficial if they could speak but “the back to front nature of it” is that most officers feel that they cannot speak.

Another firearms officer went further and said that it would be “completely alien if you even spoke to a supervisor for advice or support or help”. He added: “If you are struggling, it is like ‘they have lost the plot, get rid of them… they can’t be on this department’ […] Y’know, damaged goods type of thing. You feel like you are going to have a black mark against your name and that people won’t know how to deal with you […] You can’t be honest here, because it will just wreck your career.”

But anger is acceptable

Worryingly the police officers I spoke to told me that one emotion that was deemed to be OK was anger – despite this being specifically identified as unacceptable behaviour in the police Code of Ethics. This exception was expressed a number of times by officers and was explained by one detective who said aggression between colleagues was a regular occurrence.

They described one “bust up” between three officers over an arrest, adding: “It caused quite a lot of conflict for a long time where, I couldn’t speak to them […] it was absolutely disgusting and out of order but this sort of thing goes on all of the time.”

Such permissible negative behaviour between colleagues breaks down relationships and isolates officers, further reducing the potential for officers to open up about their emotional experiences with one another, effectively removing a main source of social support.

Perhaps the most telling diary entry about emotional support came from a response officer. He said emotion essentially equalled weakness. You simply cannot express how you feel. “Emotions and mental health and wellbeing within my force is just disgusting,” he said. “Nobody cares. I am just a number, I have acknowledged that. It is only a job and it pays the bills and I have sort of embraced that in a way and let things go a little bit.”

Others agreed with statements like: “No one ever tells you that actually… it is completely normal to be scared… it is a kind of pride thing.”

Again, participants spoke of the need to hide their feelings at home so as not to burden family with worries. One detective inspector said he did this because “it was easier to just put it in a box at the end of the day”. Some of the things that he “put in box” were from 30 years ago and are still there. But he said they remained “stuck in my mind”.

Another detective told me a story from early in his career. He was with an elderly couple. The man had just died and the woman was saying goodbye to him.

“I felt as though I should be showing a sort of quiet, detached, emotionless state of professionalism. I felt so sad, but I didn’t feel as though I could show that to her, so I showed her nothing,” he said.

But he was unable to keep suppressing what he was feeling and eventually he broke down in front of her.

He said: “I couldn’t hide my emotions anymore… I was now crying, and I will always remember that she looked at me and said, ‘you look like you need a hug’. I just felt that by not keeping my emotions in check… that I had somehow failed her.”

In many ways this officer had a perfectly normal reaction to a traumatic experience. He empathised with a bereaved woman, felt her pain and wept. The bottled up emotion was released. Yet, he felt a failure because of it.

Numb

What this all leads to is officers actively trying to dissociate from their feelings. Or as one officer put it, “trying to turn myself into that numb person”. And not just when they are at work with the public but back in the station with their colleagues and back at home with family and friends.

It turns out that a social expectation of how officers behave, or more to the point, how their brains work, means they feel unable to express their emotions. This is a key contributor to PTSD. It also is not a great way to police our communities and can have wide reaching consequences.

The police service and the public all ask for officers to be empathetic but this expectation that they suppress their own emotions means they are less emotionally aware and less emotionally intelligent and compassionate as a result – both with themselves and others. One particular quote from the diaries hit home on this point. It was from an inspector who said: “You can’t be yourself […] it is a lonely place to be. It is a very lonely place to be.”

Police officers need to be able to express emotions, other than anger, if we are to have a police service capable of dealing with the kinds of crimes and social problems seen today.

The police service has the ability to prevent the high numbers of PTSD through a change in culture – but needs the support of the public.

Officers need permission to be fully functioning, empathetic people. People who chose to join the police to protect others because they care about the community in which they live. Yes, care. That is an emotional response too, and there is no shame in that either.

Sarah-Jane Lennie is a chartered psychologist and researcher in Decent Work and Productivity at Manchester Metropolitan University. She lectures in Business Psychology, specialising in emotions in the work place and mental health and well-being. Prior to returning to academia she served for 18 years as a police officer, to the rank of detective inspector in both Hampshire Constabulary and Greater Manchester Police. She is an Associate to the College of Policing, as a subject matter expert in mental health and organisational culture. She is also an ambassador for Police Care UK, a charity supporting police officers and their families. Her research focuses on supporting police officer’s emotional wellbeing through the exploration of officer’s lived experience and the impact of organisational culture on individual mental health. She looks at the role of stigma, emotional suppression and dissociation in the increasing cases of PTSD within our officers.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/a-culture-of-silence-and-stigma-around-emotions-dominates-policing-officer-diaries-reveal-152657