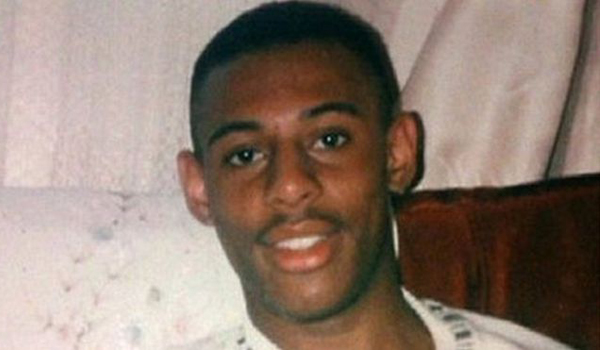

Stephen Lawrence: Timeline of a policing legacy that changed the collective conscience of a nation

The investigation into a cowardly crime “committed for no other reason than racial hatred” may have been greeted with an almost deafening silence by an indifferent nation a quarter of a century ago – but the legacy left by the life and death of Stephen Lawrence knows no parallels.

The investigation into a cowardly crime “committed for no other reason than racial hatred” may have been greeted with an almost deafening silence by an indifferent nation a quarter of a century ago – but the legacy left by the life and death of Stephen Lawrence knows no parallels.

The impact on British policing has been gargantuan, laying a lasting footprint over the way justice is perceived and proving a watershed in race relations.

This Sunday (April 22) sees the 25th anniversary of the brutal killing of an “innocent 18-year-old on the threshold of a promising life”.

His murder and initial investigation in 1993 led the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) to be labelled “institutionally racist” and castigated for a “collective failure of an organisation to provide a professional service … through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people”.

It took more than six years and a public inquiry before Sir William Macpherson reached that conclusion in February 1999 – during which time Nelson Mandela met Stephen’s parents Neville and Doreen Lawrence to publicly state that their son’s murder showed that “it seems black lives are cheap”.

The Macpherson report made 70 recommendations, of which 67 had produced specific changes in practice or law within two years of publication.

They spawned both the scrapping of the rules on double jeopardy and the creation of the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC).

And at the start of the new Millennium, as a cornerstone of a post-Lawrence ‘affirmative action’ programme, the 1976 Race Relations Act extension removed legal immunity for individual officers – bringing policing into line with the kind of anti-discrimination disciplines which had been spreading change through private industry and local government over the previous two decades.

As Stephen’s cousin, Matthew Bickley, says of the legacy left behind. “There is the England before Stephen Lawrence and the England after.”

The anniversary has led to an outpouring of grief possibly as great as followed the tragedy, and in soul-searching terms an even greater desire to look within and seek to challenge the status quo to the promise of brighter days ahead.

The timeline of events begins with Stephen’s birth and runs through to last week’s three-part BBC documentary called <i>Stephen: The Murder That Changed A Nation </i>which revealed the breakthrough moment of Operation Fishpool when detectives realised Stephen had not been subjected to a “brief” attack lasting a few seconds but a brutal, sustained assault of up to 50 seconds.

“That revelation was probably the catalyst for solving the whole case,” said Fishpool’s senior investigating officer (SIO), retired Detective Chief Inspector Clive Driscoll.

Advanced DNA techniques then came to the aid of forensic investigators to link two of the suspects’ clothes to the victim’s blood.

Original prime suspects Gary Dobson, now 43, and David Norris, 41, were finally convicted and sentenced in January 2012.

Both were given life terms with Dobson to serve at least 15 years and two months, while Norris received a minimum of 14 years and three months.

TIMELINE: Stephen: The Murder That Changed A Nation

September 1974

Stephen Lawrence was born on September 13, 1974 at Greenwich District Hospital in south east London to Neville and Doreen Lawrence, a couple who moved to the capital from Jamaica in the 1960s. The family grew up in Plumstead and from an early age Stephen wanted to be an architect.

1983

Police Federation chairman Leslie Curtis is questioned on television whether an officer should be dismissed for calling a black man a n*****. “Why”, he asks and replies: “Indeed, no.” Asked if he considers the remark is abuse, he answers: “That’s a matter of opinion.”

April 22, 1993

Stephen Lawrence attacked by a pack of white, racist youths as he waited at a bus stop with his friend Duwayne Brooks in Eltham, south-east London. Before the youths charge, they are heard to shout: “What, what n****r?” Stephen managed to drag himself 200 yards before collapsing from two fatal stab wounds.

June 1993

Police arrest brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt, David Norris, Gary Dobson and Luke Knight, and search their homes. Neil Acourt and Luke Knight are identified by Duwayne Brooks at ID parades as part of the gang responsible and the pair are charged with murder. They deny the charges.

July 1993

Charges are dropped by Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) as it says ID evidence from Mr Brooks “unreliable”.

December 1994

Stephen’s parents bring a private prosecution against Gary Dobson, Luke Knight and Neil Acourt.

April 1996

Their attempt fails when Mr Brooks’s ID evidence was declared inadmissible.

April 13, 1997

Inquest into death of Stephen Lawrence resumes and the five suspects refuse to answer questions. A verdict of unlawful killing “in a completely unprovoked racist attack by five youths” is delivered.

April 14, 1997

Next day, the <i>Daily Mail</i> goes to the unprecedented lengths of naming the five men on its front page, calling them ‘Murderers’. It urged the men to sue the newspaper if the headline was wrong. The decision to take such a legal gamble is discussed in the documentary by Mail editor Paul Dacre. He admits the newspaper may never have run the infamous headline and story if the teenager’s father, Dr Lawrence, had not performed “excellent” plastering work at his home.

March 1997

Kent Police launches its inquiry into MPS conduct, which nine months later highlights “significant weaknesses, omissions and lost opportunities” in the investigation but dismisses evidence of racist conduct.

July1997

Home Secretary Jack Straw announces Sir William Macpherson will conduct a public inquiry into MPS investigation of Stephen Lawrence murder.

Jack Straw tells the documentary in April 2018: “As the police authority for London and also Home Secretary I was the final court of appeal for police discipline cases. That meant I had a window on the actuality of police corruption. There were some staggeringly corrupt police officers around at that stage. Corruption inside the Met and quite a number of other big police services had been endemic in parts of their CIDs.”

March 1998

Macpherson inquiry opens in Hannibal House, above south London’s Elephant and Castle shopping centre. The five suspects are told to give evidence or face prosecution. In June, they appear and are pelted with bottles by protesters as they leave, after being accused of being evasive.

July 1998

MPS Commissioner Sir Paul Condon issues a personal apology to the Lawrences for force “failings” in the murder investigation. The family calls on him to resign.

February 1999

A total of 70 recommendations from Macpherson report which concludes: “There is no doubt but that there were fundamental errors. The investigation was marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership by senior officers.”

September 2002

David Norris and Neil Acourt jailed for 18 months for a racist attack on an off-duty police officer in Eltham in 2001. Norris, a passenger in a car driven by Acourt, threw a drink and shouted racist abuse at the black officer.

2004

The creation of the Independent Police Complaints Commission was considered to be a response to the Lawrence family’s frustrations with the justice system and Macpherson’s recommendation that allegations against the police be investigated by a body that was separate from it.

May 2004

CPS rules out trial at end of Operation Athena due to insufficient evidence and hands Mrs Lawrence a letter to read, failing to explain ‘in person’ the reasons for the decision.

Cressida Dick tells the documentary in April 2018: “Officers were so driven trying to bring people to justice. We took the case to the CPS but the decision was one of insufficient evidence to prosecute. This was clearly a huge disappointment to them [the Lawrences]. I can’t put myself in their shoes. It was very hard when the decision came from the CPS.”

2005

Double jeopardy scrapped, ending 800 years of legal history.

June 20, 2006

Det Chief Insp Clive Driscoll takes over as SIO for Operation Fishpool. He explains it only comes about after he is asked to clear up a room in Deptford police station that was being closed. He discovered files relating to the Stephen Lawrence case and was told to “bin ‘em”. He tells the documentary he went to see Cressida Dick and “persuaded” her to continue the investigation.

The SIO rewalks the murder route with Mr Brooks who discovers the street landscape has changed and organises a re-enactment. While checking statements the officer discovers the attack was far from “brief”, adding: “It was nothing like it. It could have been as long as 45 or 50 seconds. A brief attack would be five seconds, a whack on the nose and away. That revelation was probably the catalyst for solving the whole case.”

November 2007

MPS confirms it is investigating new forensic evidence and the review, staffed by 32 officers launched the previous summer, is looking at opportunities to use new technology to find leads.

The investigating team enlists the support of Angela Gallop, chief executive of LGC Forensics. “She had a much wider view of what should be being done,” said Det Chief Insp Clive Driscoll, who asked her to conduct tests as if the murder had happened that day.

Stephen Lawrence was wearing five layers of clothing on the day of his murder – a vest, polo shirt, jumper, body warmer and jacket. During the attack, a reverse action occurred with fibres from Stephen’s clothing breaking free and going onto suspects’ clothing.

“His third layer of clothing was going everywhere”, the SIO told the documentary. “It was an opportunity for the particles to go on to somebody else’s clothing.”

April 2008

While attending the London anniversary service to commemorate 15 years since the death of Stephen, the SIO was told a fragment of the victim’s blood has been found on suspect Gary Dobson’s clothing. Alison Saunders, chief crown prosecutor at the time, recalled: “Is it too good to be true? Can it stand up in court?”

February 2009

Dr Richard Stone, a member of the Macpherson panel, published a report ten years on from the conclusion of the Macpherson inquiry, pointing to “significant” police progress in reforming while claims of racism remained. Jack Straw, now Justice Secretary, says the MPS is “no longer institutionally racist”, but Mrs Lawrence alleges black Britons still being failed.

July 2010

An operation led by the Serious Organised Crime Agency snares Gary Dobson for supplying a class B drug. He is sentenced to a five-year prison term.

September 2010

Gary Dobson and David Norris charged with Stephen’s murder.

May 2011

The Court of Appeal decides there is enough new and substantial evidence to allow Dobson’s acquittal to be quashed and the case proceeds.

November 2011

Trial of Dobson and Norris begins at the Old Bailey where the jury hears that Stephen’s DNA was found on the defendants’ clothes. In the case of Dobson it was a microscopic stain of Stephen’s blood on his jacket – drying almost instantly.

Fibres from Stephen’s clothing and hairs found on both the defendants’ garments which had a 99.9 per cent chance of belonging to the murdered teenager.

Mr Justice Treaty describes the attack as a “crime committed for no other reason than racial hatred”, adding: “A totally innocent 18-year-old youth on the threshold of a promising life was brutally cut down in the street in front of eye witnesses by a racist thuggish gang.”

January 2012

Nearly 19 years after the killing, Dobson and Norris were given life terms with the former jailed for a minimum of 15 years and two months and the latter 14 years and three months. The three other men who have consistently been named as suspects but never convicted are Jamie Acourt, 41, from Bexley; his brother Neil Acourt, 42, who uses his mother’s maiden name Stuart, and Luke Knight, 41, both from Eltham.

The judge commends Det Chief Insp Driscoll for his actions.

Cressida Dick tells the documentary in April 2018: “When the verdict came through not just in the Met but in police stations around the country people told me there was cheering. People saw it as a great moment.”

June 2013

Prime Minister David Cameron calls for an immediate investigation into reports the MPS wanted to smear Stephen Lawrence’s family. Former officer Peter Francis claimed he went under cover to infiltrate the family’s campaign for justice in 1993, telling Channel 4’s <i>Dispatches</i> programme he was looking for “disinformation” to use against those criticising the force. The MPS deny the allegations and no records exist to the contrary.

October 2013

Doreen Lawrence offered seat in the House of Lords as a Labour Peer and becomes Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon.

March 2014

A review into the original murder investigation – by barrister Mark Ellison – finds that an undercover MPS officer worked within the “Lawrence family camp” while an inquiry into the handling of the murder was under way. Mr Ellison and Operation Herne unearth serious historical failings in undercover policing practices but state that officers were tasked with infiltrating groups that associated themselves with the Lawrence campaign, not the Lawrence family.

Then Home Secretary Theresa May tells the BBC documentary: “There was concern that in some quarters perhaps police officers felt in some sense they were above the law and that in a sense they didn’t have to operate to the same rules as everybody else. People need to have confidence in the police and in talking to Doreen it was perfectly obvious that confidence had gone.”

June 2014

Det Chief Insp Driscoll retires from the MPS after 33 years’ service, amid claims by the Lawrence family that it is the “clearest sign yet” the MPS is winding down the murder inquiry.

March 2015

Mrs May appoints Appeal Court judge Lord Justice Pitchford to head an inquiry into undercover policing and the operation of the MPS’s Special Demonstration Squad. Under the Inquiries Act 2005, Lord Justice Pitchford will have the power to compel witnesses to give evidence, said the Home Office.

October 2015

The National Crime Agency (NCA) starts investigation into alleged police corruption during 1993 murder inquiry – prompted by the findings of the 2014 Ellison review.

March 2016

The IPCC finds ex-MPS Commander Richard Walton would have had a case to answer for misconduct after meeting an undercover police officer during the Stephen Lawrence inquiry. Mr Walton says the force had rejected the findings and “did not plan to bring misconduct proceedings”.

April 2018

The MPS admits the inquiry into the racist killing of teenager Stephen Lawrence is “unlikely to progress further”.

The force believes that despite countless public appeals, the “rigorous pursuit” of all remaining lines of enquiry, numerous reviews and “every possible advance in forensic techniques”, the inquiry is at a stage where, without new information, it has nowhere else to go.

Stephen’s mother tells the <i>Daily Mail</i> that it was now time to call a halt to the investigation, asking what was the point of carrying on the inquiry while his father, Dr Neville Lawrence, tells <i>BBC News</i> he would accept the inquiry being scaled back but believed it should not be completely closed.

MPS SIO Chris Le Pere said: “We understand that 25 years is a poignant anniversary of the tragedy of the murder of Stephen, and our thoughts remain very much with those who loved him and feel his loss,” but insists there is still the opportunity for someone who knows what happened that night, to have a conscience and come forward.

Doreen Lawrence ends the 2018 documentary: “I didn’t set out to make a difference. We were pushed into the limelight. We didn’t have a choice. The end game was always to get justice.

“But I don’t think we’ll ever get to the bottom of corruption. The justice system won’t allow those things to be investigated in a way to get to the truth.”