Senior figures have called for an end to the stigma of mental health

Police organisations and leaders have called on everyone in policing to play a part in the welfare of their colleagues and ask: “Are you OK?”

The Police Federation of England and Wales (PFEW) says mental health in policing must be treated as seriously as physical safety.

It has launched new campaign today (February 6) to coincide with ‘Time to Talk Day’ – a national awareness day to get people talking and break the silence around mental health problems.

The PFEW campaign asks officers to be on the lookout for signs that colleagues might be struggling with their mental health, or even be one of the 25 per cent of emergency workers who have considered taking their own life.

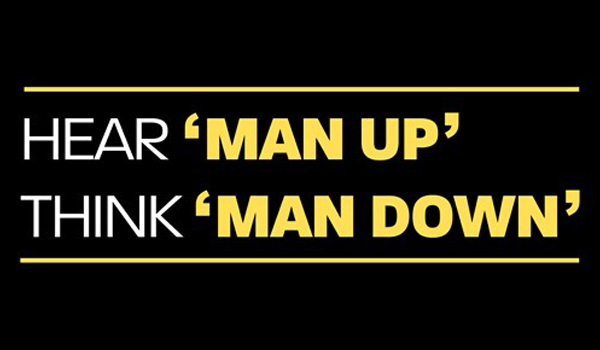

Hear ‘Man Up’, Think ‘Man Down’ urges officers to look deeper and consider whether a colleague being told to ‘man up’ in fact genuinely needs help.

Launching the campaign, Belinda Goodwin, PFEW’s wellbeing subcommittee secretary, said: “We want to get cops to talk to one another, it’s as simple as that, and to take notice when they see changes in any of their colleagues – not to ignore the signs, and worst of all tell them to ‘man up,’ get over it or pull themselves together. The campaign will build awareness of what signs to look out for and signpost to where officers can get help if they need it.

“If we can just get our members and reps to face any issues and seek help, then it can only be a good thing.”

PFEW chair John Apter added: “Life is hectic, challenging and full on! Now and again we need to pause and take a breath, remember what’s important and talk. Taking time to talk matters, more than we sometimes think. Small things can make a big difference.”

The PFEW says that to date it has been difficult to determine the actual number of police officers who take their own lives. Police forces have not routinely collected this data, and although the Office for National Statistics (ONS) collects data based on coroners’ verdicts, the figures often exclude either non-residents and/or police community support officers. It is also unclear whether retired or former police officers are routinely included in the figures. Latest ONS figures show that 66 police officers took their own lives between 2015 and 2017.

Although significant improvements in mental health support have been made in recent years, the PFEW continues to press the Government and police forces to provide earlier, better and more consistent support.

“Between 2015 and 2017 more than 20 police officers took their own life every year. That’s almost two a month. Something needs to change,” says the PFEW.

“Research has shown that emergency services workers are twice as likely than the public to identify problems at work as the main cause of their mental health problems, but they are also significantly less likely to seek help.

“We need, once and for all, put the idea that talking about emotional or mental health is a sign of weakness behind us. Police officers are dying because they aren’t asking for or getting help. They don’t need to ‘man up’, they need to speak out.

“With a quarter of emergency service workers admitting to thinking about taking their own lives, this campaign encourages officers to take each others mental wellbeing as seriously as they take each others physical safety, and questions whether we are too dismissive of colleague who may be showing signs of mental health issues – something that has potentially fatal consequences. When you hear ‘man up’, think ‘man down’ and offer help.”

Matthew Scott, the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners (APCC) lead for mental health, has blogged in support of the PFEW campaign, encouraging people to talk about this issue.

The police and crime commissioner (PCC) for Kent explained how last year he was speaking with an MP by phone about a few issues, and at the end of the call they asked if he was OK.

“I said that I was,” said Mr Scott. “The MP texted me afterwards and said: ‘Are you sure you’re OK?’

“And honestly, I really wasn’t. We had lost our beloved grandfather and I perhaps realised at that point the bereavement was impacting me more than I had thought, and in different ways. The prompt of asking again had made me think.

“Much has been said in recent years about how the stigma around mental health has been lifted.

“Certainly, policing is one area where much progress has been made. And while there is still more to do, forces are better than ever at understanding the stresses and challenges their officers and staff face in keeping our communities safe.

“PCCs recognise we have to look after the wellbeing of those who we ask to look after us.”

Mr Scott said the APCC has been championing initiatives, such as the Blue Light Programme, and investing in additional resources to manage demand and boost morale.

“In areas where PCCs have used money from their commissioning budgets to support mental health crisis services, we have shown that early intervention and community-based services can make a real difference,” he added.

“These local successes are a cause for celebration, but we should not fall into the trap of thinking that the battle has been won. Policing is leading the way, but other institutions have been slower to face up to what is required. PCCs have a role to play in challenging our partners – in holding them to account on behalf of our communities.”

Mr Scott said ‘Time to Talk Day’ encourages individuals to do their bit, too, by striking up conversations.

“Getting better at chatting to colleagues, friends, neighbours and family is how we continue to make progress,” he added. “Not sure about someone’s social media status? Pick up the phone. Or drop them a message. Drop a link to someone you’ve not spoken to for a while.

“And don’t be afraid to ask: ‘Are you sure you’re OK?’ It might make a big difference.

“Let’s continue to champion and continue to change. There’s always time to talk.”

The PFEW campaign and ‘Time to Talk Day’ have particular significance for Nottinghamshire Police Inspector Craig Nolan.

He has shared his own story as part of the campaign to show others that they are not alone. Whether it is police officers or members of the public, he believes that everyone has their own struggles and that it is important to talk.

“If you don’t talk to people, they can’t read your mind,” Insp Nolan said. “Our officers are sorting out people’s lives but they also have their own challenges.”

Although he felt that the police was “his calling” for a personal reasons, Insp Nolan found that other people’s problems brought up difficult emotions of his own.

The 47-year-old said: “Growing up, I had a difficult childhood. I thought it was normal, but I noticed that my friend’s lives were a lot calmer and less fearful than mine was. I joined the police to stop other children from going through the trauma that I had gone through.”

He remembers one incident, in particular, which was a turning point for his mental health.

“In 1997, I dealt with a case where a young boy was in a situation similar to what I had gone through”, said Insp Nolan. “I thought ‘this is exactly why I’m here’. But afterwards it sent me into a crash – so many memories I had hidden away started to come out.

“My behaviour at work was changing, I was less patient, less happy and I was drinking more. I’m always the loudest person in the room and my sergeant noticed something was wrong. That’s when I first had counselling through the police.

“When I saw the therapist all the emotions from the past were coming out. I was a mess, crying and shaking. So I had to develop a coping strategy. I was confident but I was scared. I’m a big guy and I’ve always tried to build a shell around me so I can’t be hurt.

“Part of the trauma from my childhood was me thinking I’m not good enough and that I can’t achieve anything. I’m constantly trying to prove to that inner demon that I’m better than that.”

Insp Nolan understands why men, in particular, might find it more difficult to speak out.

“As men we tend to be very quiet and just get on with it, because it’s seen as a strength to be able to control our emotions,” he said.

“It’s getting better – I think we’re talking more. I never would have spoken about this ten years ago. In the police we’ve come to a point now where we care so much for each other that those walls are being knocked down.”

While there is support for police officers who have dealt with difficult incidents, Insp Nolan feels it is also important to create a caring workplace where people feel able to be open.

“I’ve created an environment where people in my team want to talk to me. Had I not had the support myself, I might not have seen the value in doing that,” he said.

Although police work presents specific challenges, Insp Nolan has also struggled with personal issues, such as marriage breakdown, which have had an additional impact on his mental health.

“Whether you’re a police officer or not, the help is there”, he said. “I’m certain that with this change in culture, more and more people will seek support to help them through the chaos that life sometimes throws at us.”