MPs push for controversial 'thought police' Bill

MPs have called for the Terrorism Act to be extended to cover the expression of support.

Currently, the 2000 Act does not prohibit the expression of views or opinions, no matter how offensive, but only the knowing invitation of support from others for a proscribed organisation.

A Public Bill Committee on June 28 debated whether clauses within the Terrorism Act should be changed to widen the scope under which the intent for others to join a proscribed organisation is a criminal offence.

An amendment was proposed to the Act so an individual is guilty of an offence if that person “is reckless as to whether a person to whom the expression is directed will be encouraged to support a proscribed organisation.”

Labour MP Nick Thomas-Symonds argued that under the current legislation “there are others acting in a clearly unattractive way whom we wish to extend the law to”.

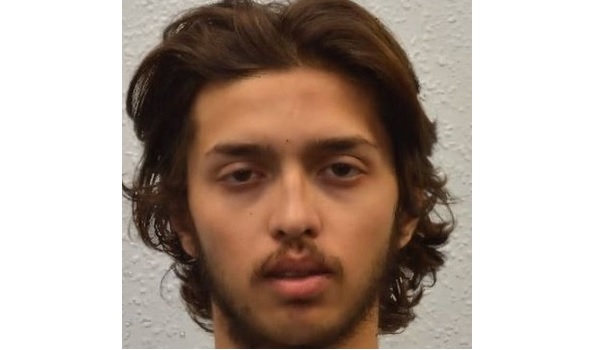

Mr Thomas-Symonds used the example of Khuram Butt, one of the London Bridge attackers, who features in Channel 4 documentary ‘The jihadis next door’. Butt was known to the police and MI5 after receiving a concerned call regarding his extremism.

However, investigations into Butt’s activities established nothing that could warrant his arrest under the Terrorism Act.

The proposal to extend the Act was criticised by human rights campaign group ‘Liberty’ which argued that this extends the criminality too far.

A Liberty spokesperson said: “While recklessness is a common legal test in some areas of the criminal law, including offences against the person, it is not an appropriate standard for criminalisation when applied to speech.”

Liberty pointed to the Joint Committee on Human Rights’ conclusion in 2006 that “speech does not naturally reside in the realm of criminality. This is why the element of intention should always be attached to speech offences.”

It added that the change in law may end in prosecutions for those merely discussing whether a group should be proscribed or not. This could be especially problematic for when a group changes its aim.

Corey Stoughton, Advocacy Director of Liberty, told the Committee on June 20: “When you attach recklessness to the expression of opinion or the expression of any protected activity, you exacerbate the chilling effect that that has on behaviour, because you no longer have to establish the subjective intent to engage in something which the Government consider to be dangerous. You can merely be playing in a dangerous area and expressing an idea, and if the idea is interpreted as support for Hezbollah, or for a Kurdish group that may be engaged in terrorist activity, or for any of the number of groups that are constantly changing their alliances in Syria, and you suddenly run afoul of the criminal law, that is a very dangerous development.”

However, Minister of State for Security Ben Wallace insisted that the Bill was to close a vital gap. “Critics have used the phrase ‘thought police’. Obviously, we are trying to grapple with the threat from inspiring – people who do not specifically stand up and say, ‘Join ISIS’, but use their position recklessly to promote such organisations by saying, ‘I think they are great’.”

Rachel Robinson, Advocacy and Policy Manager at Liberty, said: “These proposals would make thought crime a reality. It is already an offence to plan acts of terrorism or join a terrorist group. Blurring the boundary between thought and action by locking people up simply for exploring ideas undermines the foundations of our criminal justice system. It will criminalise innocent people, chill free speech and curb journalistic and academic inquiry.

“Terrorists’ primary goal is to undermine our freedom. With proposals like this, the Government risks giving them exactly what they want.”