Mass facial recognition roll-out a ‘legal grey area’, says report

The UK’s fragmented and piecemeal approach to governing facial recognition and other biometric technologies is failing to provide legal certainty or safeguard the public, according to a new report published by the Ada Lovelace Institute today (May 29).

The Institute is urging government to pass new risk-based legislation amid rapid expansion of the technology’s use across both the public and private sector.

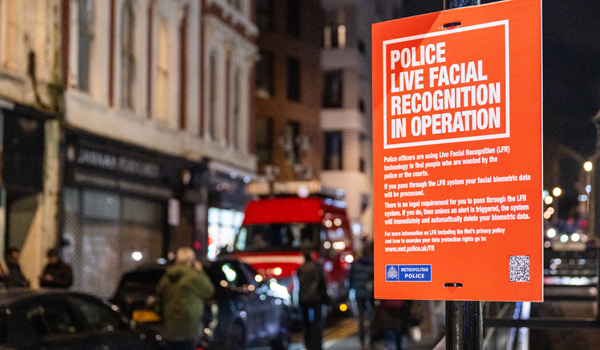

Almost 800,000 people have had their faces scanned by the Metropolitan Police Service since 2020 and the UK’s first permanent facial recognition cameras are set to be installed in Croydon later this year. The Home Office has confirmed that it has spent £3 million on ten new live facial recognition vehicles for future deployment.

Deployment of these technologies is rapidly expanding beyond police use and beyond just identifying people. Biometric technologies have also been used in train stations to monitor passenger behaviour, in schools for cashless payments and in supermarkets to identify shoplifters.

A new generation of biometric technologies claim to remotely infer people’s emotions, attention levels or even truthfulness – raising major concerns about accuracy, ethics and legality, says the Ada Lovelace Institute.

Michael Birtwistle, associate director at the Ada Lovelace Institute, said: “The lack of an adequate governance framework for police use of facial recognition – one of its most visible and high-stakes applications – is doubly alarming. It not only puts the legitimacy of police deployments into question, but also exposes how unprepared our broader regulatory regime is, just as deployment is accelerating and expanding into risk-laden new uses such as ‘emotion recognition’.”

“If we can’t establish proper safeguards for police use of live facial recognition – arguably the best governed use case – then we know people are even less protected from the impacts of private sector surveillance and invasive newer applications that try to predict people’s sensitive internal states. Policymakers must act to provide legal clarity and protect people and society.”

He said the need for legal clarity and effective governance has never been greater, but many, including parliamentary committees and the former Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner, have raised serious questions about whether the UK’s current approach to governance is fit-for-purpose.

In 2020, the Court of Appeal ruled in Bridges v South Wales Police – the UK’s only case law on live facial recognition (LFR) to date. The judgment found LFR use had been unlawful, highlighting ‘fundamental deficiencies’ in the legal framework and setting out mandatory standards and practices for lawful police use.

Since then, a fragmented patchwork of voluntary guidance, principles, standards and other frameworks has been developed by regulators, policing bodies and government to govern the police use of live facial recognition.

However, new analysis from the Ada Lovelace Institute has found this patchwork of governance is inadequate in practice, creating legal uncertainty, putting fundamental rights at risk and undermining public trust. The research finds that beyond police LFR use, the governance arrangements for all other prevalent biometrics deployments are subject to even less adequate governance, leaving their lawfulness in serious question.

Public engagement research by the Institute has also found that there is a clear public expectation for legislation and independent oversight governing the use of biometric technologies.

The Institute is calling for risk-based legislation covering both the private and public sector, with oversight and enforcement by an independent regulatory body. The proposed legislation should introduce tiered legal obligations based on the risk posed by each biometric system – similar to the EU AI Act – and empower the regulatory body to issue binding codes of practice for different use cases.

Nuala Polo, UK Public Policy lead at the Ada Lovelace Institute said: “There is no specific law providing a clear basis for the use of live facial recognition and other biometric technologies that otherwise pose risks to people and society. In theory, guidance, principles and standards could help govern their use, but our analysis shows that the UK’s ad hoc and piecemeal approach is not meeting the bar set by the courts, with implications for both those subject to the technology, and those looking to use it.

“Police forces and other organisations claim their deployments are lawful under existing duties, but these claims are almost impossible to assess outside of retrospective court cases. It is not credible to say that there is a sufficient legal framework in place.

“This means the rapid roll-out of these technologies exists in a legal grey area, undermining accountability, transparency and public trust – while inhibiting deployers alive to the risks from understanding how they can deploy safely. Legislation is urgently needed to establish clear rules for deployers and meaningful safeguards for people and society.”