Call for inquiry as PCCs power to remove chief constables deemed ‘corrosive’

The power of police and crime commissioners (PCCs) to remove chief constables from office is having a “corrosive” effect on policing and police accountability, according to research by the University of Essex.

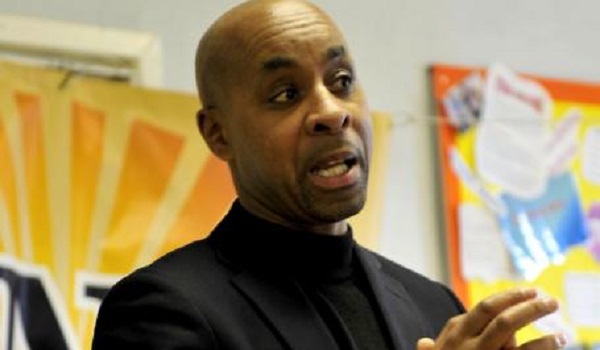

Dr Simon Cooper of the university’s School of Law says this could not only cause “instability in police leadership and a potential culture of compliance”, but could also see chief constables becoming “indebted” to their PCC.

He is calling for a select committee inquiry to re-examine the system for holding chief constables to account.

Dr Cooper said he gained “unprecedented access” to key figures from all sides for his research, interviewing PCCs, chief constables and members of police and crime panels (PCPs) in five police forces, as well as the person responsible for introducing the current system and one of the most senior persons in policing at a national level.

“The interviews conducted for this research find the PCC’s power to remove their chief constable has already compromised the independence of these senior officers,” he said. “As currently formulated, the PCC’s section 38 power creates an environment in which it would be possible for a PCC – effectively a lay person – to command, overrule and potentially even control a chief constable. We urgently require a select committee inquiry to re-examine a PCC’s power to remove their chief constable.”

Dr Cooper said the introduction of elected PCC’s in 2012 was a key element of then Prime Minister David Cameron’s ‘Big Society’, billed as the replacement of an outdated bureaucracy with devolved, democratically-accountable oversight.

Section 38, which gives a PCC the exclusive power to remove their chief constable from office, and to exercise a broad discretion in reaching this decision, was seen as vital to delivering accountability.

Dr Cooper’s research, published in the Criminal Law Review, identifies two new areas of concern.

“First, a PCC’s ability to remove their chief constable could cause an instability in police leadership and a potential culture of compliance, as chief constables – many close to retirement – avoid conflict with their PCC,” he said. “The ease with which a PCC could remove a chief constable – contrasted with the complex process for removing a PCC – is seen as having resulted in a concentration of power at odds with the principles of good governance.

“Second, chief constables could be developing a practice of abstention and risk becoming indebted to their PCC.”

Dr Cooper said senior figures he interviewed also noted a “ripple effect” at the rank of chief constable, as progression to the most senior rank is no longer seen as attractive.

He added that one PCC he interviewed noted: “There has been a power shift; it’s a significant change and it’s no surprise that about half of the chief constables have gone.”

As part of a review of section 38, Dr Cooper suggests that the currently limited powers of PCPs could be increased, a code of practice introduced and the Policing Protocol amended to encourage PCPs to proactively seek the professional advice of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Service when a PCC decides to remove a chief constable.

Dr Cooper said the section 38 power has proven highly controversial: “In May 2013, the House of Commons Home Office Committee argued it was ‘operationally disruptive, and costly, and damaging to the police and individuals concerned’. In the same year, the Stevens Review suggested that this power risked ‘exerting a damaging chilling effect over the leadership of the police service’.”