What is a public health approach to violence?

When the Home Office provided funding to 18 areas of the UK to establish Violence Reduction Units, it specified the requirement that a ‘public health approach’ should be taken. All of these areas have sought to define what this actually means, as Rachel Staniforth and Greg Fell explain.

Some have talked about a public health approach treating violence as a disease – tracking it back to its source and looking to prevent spread (https://members.tortoisemedia.com/2019/03/09/knife-crime/content.html?sig=QThbvstgmWJ0hKkAqwu70RHVKstE0EcE14u3sEsdMOE&utm_source=Twitter&utm_medium=Social&utm_campaign=9March19&utm_content=Not_a_sticking_plaster). There are arguments that this over medicalises what is a largely social issue. Yes – a public health approach does look at the causes of the violence. And not only that, it looks at the causes of those causes.

Taking a public health approach is about going back to the very beginning. Understanding progression, then working to prevent violence across the whole spectrum of risk, at all levels (individual, relationship, community and societal).

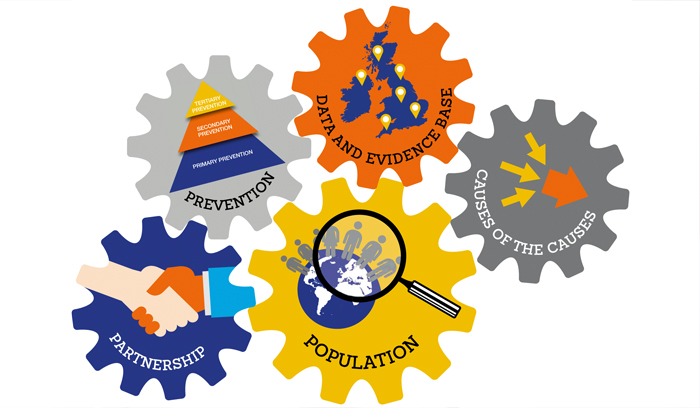

By far the best document we have come across that explains ‘a public health approach to…’ is Public Health Approaches in Policing (Public Health England/College of Policing). You can replace the ‘policing’ with just about anything. This document outlines five elements to a public health approach that we have adopted in South Yorkshire.

- Taking a population approach – it is important to understand the needs of the whole population, in order to better focus resources. Key point – need does not equal demand, and those most able to access resources are often those that need them least (and vice versa).

- Causes of the causes – understanding the determinants of violence. These are largely the same as the determinants of health, and there is a famous diagram that depicts them nicely (Dahlgren and Whitehead). As well as the social determinants, there are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), adverse community environments (together known as ‘the pair of ACEs’) and trauma – both in childhood and adulthood.

- Data and evidence base – understanding the issue is key, as is developing and strengthening the evidence base. Evidence is good at individual level, but poor at relationship, community and societal level – strengthening this is hugely important. Our area profiles are seeking to understand local issues – but these need to be continuous processes, not static documents. In South Yorkshire we are working to build a dashboard of data that can be interrogated with various questions that we want to answer (although this is a much longer term aim).

- Partnership – another requirement from the Home Office and also another incredibly important element. There is no one agency that operates across the whole system. A key role for Violence Reduction Units is to coordinate and align organisations across the system.

- Prevention – the core of a public health approach. There are three types of prevention: primary, secondary and tertiary. We are often very good at tertiary prevention – working to provide an alternative or a way out for people entrenched in violence. Sometimes we think that because we are doing tertiary prevention activities, we are ‘covering’ prevention. Or because we do secondary prevention well (things like early help or early intervention, where we aim to stop progression of issues), we are doing well at prevention. The thing we do least is what we need most – primary prevention. This is where we work to prevent violence happening right back before it was even a possibility. This is investment in young people; in communities; in services; in the welfare system; and in families. This is investment in all people – believing that all people have the same rights to a minimum standard of living.

Taking a public health approach is also about enforcement and criminal justice. Some people believe that a public health approach is ‘soft’. It is not. People must be held to account for their actions when they are criminally culpable.

We had a conversation with someone the other day who told us the answer to violence was more police on the street. A deterrent. Squash the problem. Hit them hard. We found the choice of language oddly ironic and it really highlights how much a part of our culture violence is. We asked: “How do we stop the need to ‘hit them hard’ in the first place?” No answer. We cannot arrest our way out of a social issue. Violence is a social issue.

The heart of a public health approach though, which we have not yet seen articulated, is the belief that people can change. A fundamental belief that if people want to, and are provided with the right support, tools, and environment, they can change.

Often in conversation we hear people say things like: “He had enough chances.” “She was offered support and didn’t engage.” “They made their choice.”

So when do we give up on people? When we repeatedly offer support, and for a myriad of complex reasons people are unable to accept it there and then, when is enough, enough?

How many chances do we give?

Our answer – we give as many chances as someone needs.

We keep offering them that way out, that way forward, while ensuring that people are held responsible for their actions. This is not about being lenient. This is about giving people options that they may not have had before.

At what point does a criminally or sexually-exploited child stop being exploited? Is it age 16? 18? 21? Even at age 30 there is often a history of abuse, exploitation and trauma. All with accompanying changes to brain development and impacts on mental and behavioural state. We are not saying that people who were exploited are somehow excused of their crimes – they are absolutely criminally culpable most of the time. We are saying that there is a history – and a reason. And if we believe that people can change then we will help them, rather than isolate them from society further (for example, having been in prison means that finding employment is incredibly difficult).

Often, we believe that our piecemeal bits of support will help. In truth, we must come together; as a society, as communities and as friends to help each other. To listen and to care. It reminds us of this poem:

An addict fell in a hole and couldn’t get out

A businessman went by and the addict called out for help. The businessman threw him some money and told him to buy himself a ladder.

But the addict could not buy a ladder in the hole he was in.

A doctor walked by.

The addict said: “Help. I can’t get out.” The doctor gave him some drugs and said: “Take this. It will relieve the pain.”

The addict said thanks, but when the pills ran out, he was still in the hole.

A well-known psychiatrist rode by and heard the addict’s cries for help. He stopped and asked:

“How did you get here? Were you born there? Did your parents put you there? Tell me about yourself, it will alleviate your sense of loneliness.”

So the addict talked with him for an hour, then the psychiatrist had to leave, but he said he would come back next week.

The addict thanked him, but he was still in the hole.

A priest came by. The addict called for help. The priest gave him a bible and said: “I’ll say a prayer for you.” He got down on his knees and prayed for the addict, then he left.

The addict was very grateful, he read the bible, but he was still stuck in the hole.

A recovering addict happened to be passing by. The addict cried out: “Hey, Help me. I’m stuck in this hole.”

Right away the recovering addict jumped down in the hole with him.

The addict said: “What are you doing? Now we’re both stuck here.”

But the recovering addict said: “Calm down. It’s okay. I’ve been here before. I know how to get out.”

Author unknown

Point being – we can do all the (worthwhile) sporting and social interventions with young people that we want, but if a young person is hungry because they have eaten only one meal today; went to school without showering for over a week because mum could not afford to put gas or electric on; had to help siblings get ready in the morning because mum was at work really early; and is being bullied for their trousers being too short (they’ve grown and mum can’t afford more) – being offered £50 to sell something for someone who is kind to them is a bit of a no-brainer.

For us, the public health approach is about remembering that people behave in a way that their circumstances dictate. Everyone has a choice, but some people’s choices are rather more limited than others. Taking a public health approach is about remembering that people can change, and giving people as many chances as they need, while ensuring they take responsibility for the choices they make.

Rachel Staniforth is joint head of the South Yorkshire Violence Reduction Unit – https://southyorkshireviolencereductionunit.com/

Greg Fell is Director Of Public Health in Sheffield.

Project evaluates impact of violent crime interventions

Psychologists from Sheffield Hallam University are to lead an evaluation project to “help shape the future of violent crime interventions in South Yorkshire”.

The project will assess the effectiveness of activities and interventions undertaken by South Yorkshire’s Violence Reduction Unit (VRU).

Led by Dr Charlotte Coleman and Dr Kate Whitfield, from the Forensic and Investigative Research group at Sheffield Hallam, it will allow the unit to understand the impact of its work and provide new knowledge that will inform policy and practice locally and nationally.

Established in August 2019, following a successful multi-agency bid for a £1.6 million grant from the Home Office, the South Yorkshire VRU works in partnership with a range of public, community, faith and voluntary organisations to develop and deliver a range of activities to reduce violence in the region, including a public health approach to violent crime. This month, a further £1.6 million was made available by the Home Office to enable the VRU to continue to “coordinate the local response to serious violence”.

Rachel Staniforth, joint head of the VRU, said the unit was now in its second year of funding from the Home Office and the project will provide “valuable insights into what is working”.

“In the first year we were required to produce an area profile and response strategy that look at the causes of violence in South Yorkshire. This document will be published very soon,” she said.

“Part of taking a public health approach is using and adding to data and the evidence base. We want to ensure that the work we are undertaking is having an impact.

“The evaluation that Sheffield Hallam University is undertaking will provide valuable insights into what is working well and what could be improved. These findings will add to the effectiveness of our work, ensuring that we deliver interventions and initiatives that improve the lives of young people and communities in South Yorkshire.”

A public health approach starts with the needs of the public or population group rather than with individual people. As violence is increasingly being considered a public health issue, a key component of the evaluation is to work with stakeholders and communities to assess the contribution and engagement of the VRU.

Dr Coleman said: “Our team are delighted to be working with the South Yorkshire’s VRU on such an important piece of work that will help shape the future of violent crime interventions in South Yorkshire.”

“This funding recognises the expertise of our forensic psychology team in working in the area of violence reduction and evaluation methodologies. I have no doubt that this new working relationship will open up future partnership opportunities to work alongside the South Yorkshire VRU and other crime organisations.”

The project will update the current ‘Theory of Change’ – a description of how and why a change is expected in a particular context, which guides organisational planning, participation and evaluation – and support the development of an evaluation framework for the unit to use in current and future commissioned work.

The updated Theory of Change will support the VRU in prioritising activity and understanding the impact of its work in reducing violent crime, while the evaluation framework will support it in using and developing evidence to ensure the continuation of effective working in the long term.

Based at Shepcote Lane police station in Sheffield, the unit looks to tackle the causes of violence and not simply deal with it after crimes have been committed.

Its work is overseen by a violence reduction executive board that includes South Yorkshire’s police and crime commissioner Dr Alan Billings and South Yorkshire Police Chief Constable Stephen Watson, together with representatives from all four of the region’s local authorities, health and education services, probation and youth offending teams and the faith and voluntary sector.

The Home Office has said it expects the South Yorkshire VRU “to lead and coordinate the local response to serious violence”.

Dr Billings said the additional £1.6 million funding would enable the VRU to continue its work for this financial year.

“Since we launched the Violence Reduction Fund in December we have been able to fund more than 20 projects aimed at drawing young people away from violence or helping others to break out of the cycle of crime and violence they may have fallen into,” said Dr Billings. “We shall be able to continue some of these projects and add others between now and the end of March 2021.

“I am quite clear that in South Yorkshire we must do two things. We must come down hard on those who resort to violence and the gangs where violence often breeds. But we must also understand the reasons why people are drawn to violence in the first place and find ways of steering them away from it.”

Ms Staniforth added: “During the first year, we have produced an area profile and response strategy as a requirement of the Home Office funding. The area profile looks at the causes of the causes of violence, across Barnsley, Doncaster, Rotherham and Sheffield. The response strategy details how we are going to tackle these issues and what the priorities of the partnership are.

“The funding for the 2020/21 financial year will allow us to embed these priorities and work with our partners on delivering interventions to prevent and reduce violence.”

Among the initiatives funded through the South Yorkshire Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) are ‘custody navigators’, who engage with young adults arrested for crimes that are linked to violence.

The ‘Plan B’ navigators are based in the custody suite at Shepcote Lane police station and support those ready to make positive changes in their lives, using detention as a “reachable and teachable moment” to break offending cycles.

Joint head of the South Yorkshire VRU, Superintendent Lee Berry, said it was not an alternative to the criminal justice system but was “a life choice for the individual who is trapped in crime”.

“The custody navigators will support and listen to those arrested and detained in custody. They will look to understand how they have become involved in criminality and provide help and support. This support will continue once they leave custody to help steer them away from criminality,” he added.