Countering extremism: Time to reboot?

New research by Crest Advisory shows that almost a quarter of the public have either witnessed or experienced extremism in the past 12 months, and more than half believe extremism is worse than it was a year ago, as Harvey Redgrave, James Stott and Callum Tipple explain.

Extremism is a significant and growing threat to this country. When left unchecked, extremism can incite violence, threaten the democratic institutions and norms that underpin liberal democracy, and undermine the social fabric that binds us together.

However, while there is political consensus around the urgency of tackling extremism, there remains a lack of clarity around how the government ought to respond.

Extremism occupies an ambiguous and contested space. Unlike hate crime, violence and terrorism – offences which can be defined and legally prohibited – extremism need not involve direct criminality (although it often overlaps). Ultimately, it is this subjectivity that has made the task of constructing a policy framework so elusive. Five years on from the publication of its ‘Counter Extremism Strategy’, the Government is yet to set out an agreed definition of extremism and/or the role it expects individual agencies to play in tackling it.

Nowhere is this ambiguity more starkly illustrated than with respect to the police – the primary subject of this report. Our fieldwork has revealed a worrying level of confusion about how officers ought to respond to extremism within their communities, beset by conflicting objectives and a lack of clarity as to what success looks like.

Clearly, responding to extremism cannot be the job of any one single agency or institution. Schools, local authorities, charities, the NHS, prisons – all have a role to play in combating extremism. Nonetheless, it is clear that the police – whether they are disrupting extremists, responding to hate crimes, managing extremist protests, or dealing with community tensions – are likely to represent the front line of the Government’s response to extremism. The lack of a common framework for policing extremism is thus of significant public concern. It is that vacuum which this report seeks to address.

Key findings

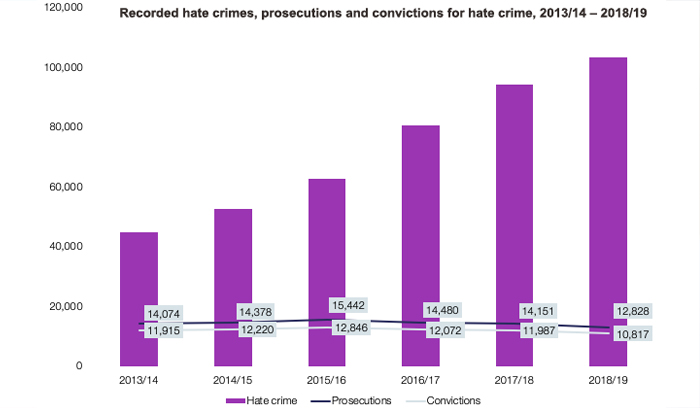

Extremism is a significant and growing threat. While the data is imperfect, multiple indicators suggest that extremism is on the rise in the UK, with increases in recorded hate crime, online toxicity and cases referred to the counter-radicalisation ‘Channel’ programme.

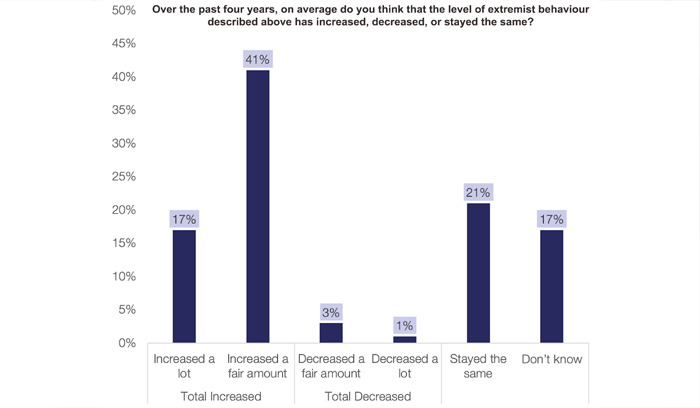

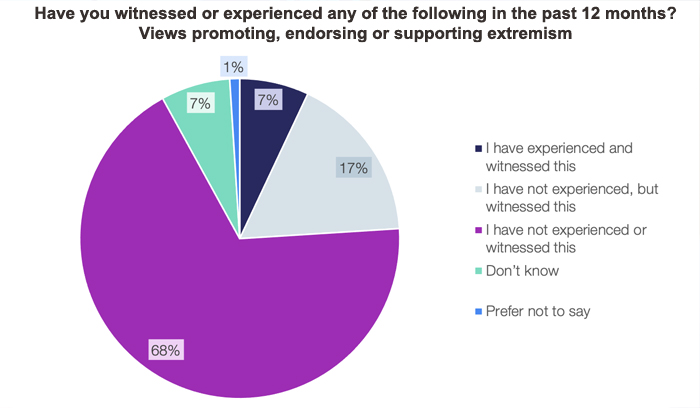

Extremism is not limited to society’s fringes: up to 24 per cent of the public have personally witnessed or experienced extremism. While attitudinal data suggests the British public has become more tolerant overall, there is evidence of a growth in extremist beliefs at the margins, in particular, with a worrying rise in anti-Muslim prejudice. New polling by Crest suggests that nearly a quarter of the public have experienced or witnessed extremism (seven per cent and 17 per cent respectively) and almost six in ten believe that extremist behaviour has increased over the last four years.

The nature of extremism has morphed over the past five years – it is more fluid and increasingly facilitated by social media, linked to a general coarsening of political discourse. Our report documents the rise in online abuse, including abuse aimed at MPs – a development that is likely to damage democratic institutions.

Despite widespread consensus around the urgency of tackling extremism, the Government has found it difficult to drive and sustain progress. This is partly because the term extremism itself is contested but also reflects a lack of joined-up thinking within government, with confusion over where counter-extremism ‘sits’ (on a spectrum between integration and counter-terrorism) and thus which departments (and agencies) are responsible for which aspects.

This has left the police confused about their role in responding to extremism. Our fieldwork has revealed officers are not clear about what constitutes extremism and what ‘good looks like’ in this area.

In many parts of the country, the police lack the required tools to sufficiently respond to extremism. Our fieldwork has revealed that many officers perceive there to be a lack of training and guidance in identifying and responding to extremism; officers are concerned about the hollowing out of neighbourhood policing and there is no national framework for the policing of extremist protests.

Principles for reform and recommendations

The UK’s ability to counter extremism has been hampered by a lack of consensus: on what extremism means, on what the Government’s response should look like and on what role the police, other agencies and civil society, ought to play. The Government urgently therefore needs to establish a new vision and strategy for countering extremism (with the previous strategy having fallen out of date). This report argues that this ought to be based on the following four principles:

- Shared understanding of the problem – a precondition for success is the ability to agree a common definition of the problem and build consensus around key priorities for action;

- Clear objectives – the Government needs to set out what it wants to achieve in relation to counter-extremism, including where counter-extremism ‘sits’ (between integration and counter-terrorism) and the role it expects key agencies, such as the police, to play;

- Accountability – it is vital that the different parts of government, and their respective delivery agencies, are clear about their own role in tackling extremism; and

- The right tools – frontline agencies (including the police) need to be equipped with the right level of resources, skills and technology to identify and respond to extremism.

In order to build a shared understanding of the problem, government should:

- Agree a common definition. The Government – and the police – should immediately adopt the Commission for Countering Extremism’s definition of ‘hateful extremism’ and task the Commission with producing an annual ‘state of extremism’ report, which is presented to Parliament; and

- Strengthen the evidence base. The Government should establish a research fund – into which universities and civil society organisations would be able to bid – to strengthen the evidence around what does and does not work in countering extremism. The Home Office should also consult on commissioning an annual survey to understand the prevalence of support for extremist ideologies across the UK and track sentiment over time.

In order to set clear objectives, the Government should:

- Publish an update to the 2015 Counter Extremism strategy, making clear where counter-extremism ‘sits’ – the updated strategy should make clear that the primary objective of counter-extremism is to prevent the risk of radicalisation. Accordingly, counter-extremism should sit within the counter-terrorism sphere, as part of a (broadened) Prevent strategy; and

- Task the College of Policing with producing and disseminating guidance on the police’s role in preventing and responding to extremism – ensuring there is greater clarity as to the police’s contribution to countering extremism and greater coordination across the 43 forces.

In order to strengthen accountability, the Government should:

- Strengthen national leadership structures – the Government should designate a cabinet minister with inter-departmental responsibility for counter-extremism to coordinate and drive progress across government. In parallel, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) should identify a national lead to coordinate work across the 43 forces.

In order to equip frontline agencies with the right tools, the Government should:

- Invest in specialist capabilities within policing – the Government should invest in a training programme for frontline police officers in identifying and responding to extremism within their communities, backed by new national guidance from the College of Policing;

- Establish a national framework for the policing of extremist protests – the NPCC should work with the College of Policing to produce guidance for forces in dealing with extremist protests and managing local community tensions; and

- Task the Commission for Countering Extremism with annually reviewing the powers required to disrupt extremists, including online.

These policies are designed to provide the basis of a comprehensive strategy that can secure public consent and, in so doing, reduce the scope for extremists to drive a wedge between communities and sow division.

This post originally appeared on the Crest Advisory website. The full report can be found here.

Harvey Redgrave is chief executive officer of Crest Advisory.

James Stott is an analyst at Crest Advisory.

Callum Tipple is senior policy analyst at Crest Advisory.