A digital dilemma

Sean Millwaters says we cannot afford to turn mobile phone evidence into a taboo subject.

One overlooked part of the UK’s controversial Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill is proposed measures designed to ensure that only information that is relevant to an investigation is taken from the mobile phones of victims and witnesses, as well as a code of practice to guide authorities on how to obtain digital evidence.

The collection and review, analysis, and management of data taken from mobile phones frequently plays a critical part in helping police forces successfully investigate crimes. However, it also attracts occasional criticism from those outside law enforcement who worry that it inadvertently invades the much-needed privacy of vulnerable victims.

The proposed measures outlined in the Bill, which is expected to be put back in front of Parliament at the end of June, are a positive step towards providing police forces with the clarity and consistency they badly need when it comes to lawfully obtaining and storing mobile phone-based evidence. It should also reassure privacy advocates who have raised concerns about so-called ‘digital strip searches’.

However, it is important that the Government ensures that public discourse surrounding the Bill does not turn the lawful access, collection and analysis of mobile phone data into a taboo subject. The ability to lawfully access the phone of a victim, witness or perpetrator quickly, combine that data with investigative analytics tools, and swiftly identify any patterns or leads, is a critical capability for any investigative team.

For example, in a 2015 murder investigation, Leicestershire Police collected and analysed call, image and location data from the iPad of missing 15-year-old Kayleigh Haywood, as well as the iPhones of two male suspects, to identify the perpetrator, elicit a quick confession, and locate Kayleigh’s body. Without access to this information, the task would have been considerably more challenging for investigators.

The role of mobile phone data in investigations is particularly challenging when it comes to sexual violence. Often traumatised victims do not want to hand over their devices, complete with deeply personal information and images, to police officers. The idea of another person trawling through their photos and messages can be upsetting, especially in the immediate aftermath of an assault.

Conversely, though, the ability of a police officer to quickly access the victim’s mobile phone data significantly increases the likelihood that an attacker will be brought to justice. This information often plays a central role in enabling the police, as well as the Crown Prosecution Service, to build a compelling body of evidence, improving the chances of an eventual arrest and conviction.

Unintended consequences

As the Government readies the Bill for its next reading in Parliament, it must be careful not to present the lawful collection, analysis and storage of mobile phone data as something that needs to be resisted or treated with suspicion. If this section of the Bill is not carefully worded and thoughtfully debated, it could have the unintended consequence of discouraging victims from handing over their devices and depriving investigators of the vital evidence needed to tackle complex cases.

For our part, technology companies working in this space also have a responsibility to adapt their digital services in order to make it easier for law enforcement agencies to comply with emerging legislation and reassure the victims of crimes that their devices will be treated respectfully. As a leading digital intelligence company, we are actively taking steps to ensure critical case information does not fall through the cracks, while ensuring victims and witnesses feel as safe and in control as possible during the process.

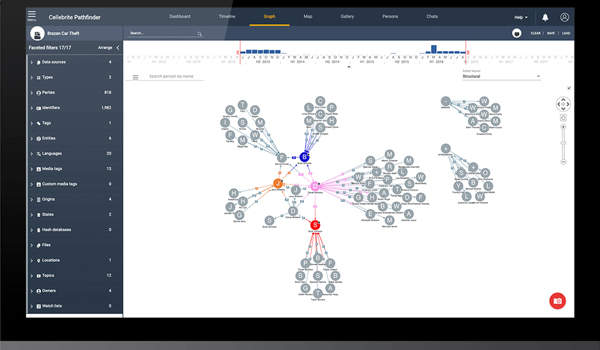

One example is the ‘selective extraction’ function that we recently introduced into our Digital Intelligence Platform. It enables investigators to reduce extensive browsing through personal data by limiting their search and collection to a specific period or keyword. It produces an audit trail that tracks which team members have accessed the data and when, as well as providing managers with transparency into who is using the hardware and the result of their efforts.

The technology also empowers police officers to perform data collection wherever the victim or witness feels most comfortable, as well as significantly reducing the amount of time they are separated from their device.

Mobile phone evidence plays a critical role in solving crimes and as these devices become more deeply stitched into our day-to-day lives their centrality to investigations will continue to grow. Law enforcement, government and technology companies must ensure the approaches to surfacing and analysing this critical mobile phone evidence are sensitive and victim-centric. A key part of achieving this is ongoing dialogue: the exact opposite of a taboo subject.

Sean Millwaters is EMEA VP at Cellebrite.