Diversionary tactics

Ellie Covell says there is an important role for out of court disposals and diversion schemes in delivering a ‘swift and certain’ justice system.

In 2019, we began a piece of research into so-called ‘swift and certain’ justice, which drew on the lessons of probation programmes in the US and sought to examine how effectively the principles behind it had been adopted by the UK justice system.

Our team found that in the past 17 years there have been at least 17 policy reforms centred on improving either the effectiveness or efficiency of the criminal justice system. Despite this, the extent to which ‘swift and certain’ justice is embedded in the system is patchy. Pre Covid-19 data shows that:

- Arrest and charge rates were decreasing, and victims were increasingly withdrawing support for the process;

- The average number of days from offence to charge increased by 71 per cent between 2011 and 2018;

- The courts had made some improvement in the average number of days between charge, first listing of a trial and its completion, but in some offences this doubled between 2011 and 2018; and

- Finally, the Prison and Probation Service had long been under strain – demonstrated by late breach and recall referrals, and minimal access to rehabilitation in prison.

It was clear long before Covid-19 struck that the criminal system as a whole was not able to intervene swiftly, and nor was detection or punishment for a criminal offence particularly likely.

With mounting concern about the scale of the backlog, it is timely to examine how the justice system has previously approached swiftness and certainty and what obstacles it encountered during these efforts. We found that there were two core motivations for the creation of a swift and certain justice system:

- Justice delayed is justice denied – Drawing on a principle laid out in the Magna Carta written nearly 800 years before, this was the opening to the Coalition Government’s Swift and Sure White paper in 2012. The idea that a well functioning justice system would indeed be swift, and punishment certain, is a commonsense principle, and something that the public rightly demands. The 2012 White Paper (in the wake of the 2011 riots) was intended to reassure the public that the system was capable of dealing with criminal activity quickly and effectively.

- Deterrence – Deterrence theory is central to the concept of ‘swift and certain’ justice. It is founded on the theory that swift responses to criminal offences or behaviours, consistently carried out, will lead the offender to an increased perception of the likelihood of being caught and punished, therefore reducing the likelihood of offending or reoffending.

However, there is also an emerging body of evidence that challenges deterrence theory, and a number of potentially conflicting objectives that must be carefully balanced.

Recent studies have shown that other factors may have a greater weighting on the motivation to commit crime other than the likelihood and timeliness of detection and punishment. The benefits of deterrence may be outweighed by the risks of ‘labelling’ (individuals as offenders). This is the idea that contact with the criminal justice system is itself a negative turning point.

Equally, the implementation of swift and certain principles must be balanced against the other pillars of our justice system – proportionality, fairness and public protection. Driving the system to progress cases more quickly through the system, for example, should not compromise procedural due process, nor should a sentencing decision made more quickly affect the proportionality of the sentence given.

With this in mind, we developed five key recommendations for the criminal justice system, which should enable swifter and more certain justice for victims and offenders alike, working to reduce offending and reoffending but without compromising the legitimacy and effectiveness of the system:

1.The police, Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and judiciary should work together to strengthen and expand the range of pre-court avenues for tackling offending, for example, through broader use of civil orders or out of court disposals and diversion. Where necessary these alternative options should be underpinned legislatively.

2.The Home Office and Ministry of Justice should establish a joint task force to review why ‘offence to charge’ times have increased and set out a joint action plan for the police and CPS to take action once these agencies have started to return to business as usual following the Covid-19 pandemic.

3.The past decade illustrates how hard it is to drive swiftness and certainty from the top down. We recommend a more devolved approach, whereby police and crime commissioners and directly elected mayors are given responsibility (and, where possible, budgets) for driving greater swiftness and certainty locally at every stage of the ‘offender journey’.

4.The end of ‘Transforming Rehabilitation’ is an opportunity to ‘reset’ the relationship between probation and the judiciary, improving the quality of pre-court advice and making it easier to bring offenders back to court when/if they breach community orders.

5.The new Justice Commission should commit to reviewing swiftness and certainty across the criminal justice system – including the efficacy of existing targets – and ensure existing measures are appropriately balanced with the principle of procedural fairness.

The role of policing

Without question, the quickest way to deliver justice is through the use of out of court disposals. On admittance of guilt offenders can be dealt with immediately by the police, negating the need to wait for a court listing, improving the swiftness of proceedings with great effect.

There are mixed views on how the certainty of punishment by means of an out of court disposal is perceived. While it clearly constitutes a sanction, some evidence suggests that victims and offenders alike can miss out by not having their day in court. In particular, from the offender’s perspective the courtroom (for some) facilitates an understanding of the gravity of the offending behaviour, which an out of court disposal cannot facilitate.

That said, the benefits are that they allow for an element of rehabilitative and/or reparative activity (which can support perceptions of certainty). And for the victim the case is closed and the offender punished in a relatively short period of time.

The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) Charging and Out of Court Disposals Strategy also highlights the benefits of victim involvement in decision-making and the condition-setting process, along with opportunities to address offender needs such as substance misuse and mental health problems through a whole system approach.

Neurocognitive research has also established a number of key parameters that strengthen learning when using punishment.

Of particular note to the use of out of court disposals is the opportunity to ensure that the offender has effectively linked the punishment being given with the behaviour that caused it. Delays between offence and punishment can mask the distinction of which action is being punished, making it more difficult to learn the association between behaviours and outcomes.

This, combined with the evidence (discussed above) that formal contact with the criminal justice system also increases the likelihood of reoffending, means that there is undeniably an important role for out of court disposals in a ‘swift and certain’ justice system.

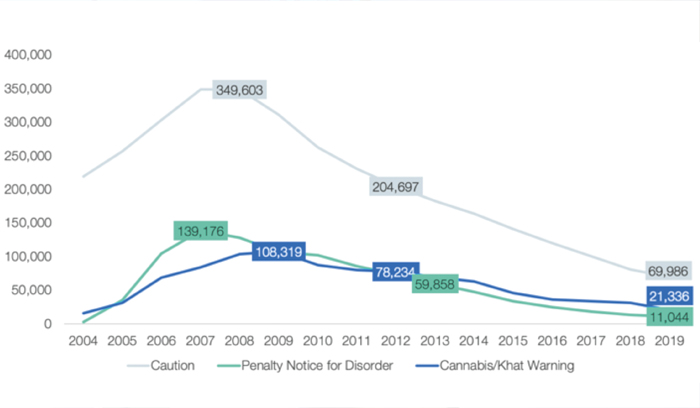

But despite this, the use of out of court disposals has declined rapidly over the past 12 years.

Out of court disposals now account for just four per cent of all crime outcomes.

The NPCC Charging and Out of Court Disposals Strategy aimed to drive up the use of out of court disposals, and sets out a blueprint for a simplified two-tier system. Many forces have now adopted this successfully.

However, there is also evidence for the use of diversion schemes – which are also newly recognised by the Home Office as recordable sanction detection for an offence.

Durham Constabulary’s Checkpoint scheme is an example of one of the first schemes set up to divert offenders from the criminal justice system.

Working one-to-one with a ‘navigator’/mentor, it offers offenders a four-month contract as an alternative to prosecution. If they complete the four-month contract, no conviction is recorded – but they are warned that if they do reoffend they will be prosecuted.

A randomised control trial study of the Durham Checkpoint scheme between 2016 and 2018 found a difference of 12 per cent in the re-arrest rate (45 per cent v 57 per cent) and a 13 per cent difference in the reoffending rate (35 per cent v 48 per cent) between the Checkpoint cohort compared with traditional criminal justice disposals.

Despite this promising evidence, diversion schemes accounted for just one per cent of all out of court disposals in the first two quarters of 2019/20.

Out of court disposals in the context of Covid-19

Over the past three months we have seen agencies across the criminal justice system rapidly adjusting operating models to the pandemic, with trials heard virtually, probation caseloads managed over the phone, and non-urgent cases put on hold across the system.

Of particular note was the guidance released by the CPS emphasising the importance of the application of the public interest code in light of the pandemic, empowering prosecutors to stop prosecutions that were not in the public interest.

Prosecutors were also asked to consider the necessity of proceeding with a case that would likely subject victims and witnesses to significant delays over the coming months and to consider whether an out of court disposal would be an appropriate response.

While there was no formal statement from the NPCC or individual forces about an increased use of out of court disposals over the period of lockdown restrictions, it will undoubtedly have been a part of the management of crime in the absence of access to other forms of justice.

The Metropolitan Police Service dashboard shows that 9,064 offences were either sanctioned (charged or dealt with by means of an out of court disposal) in the month of April 2020, compared to 5,976 in April 2019, despite the crime rate being significantly lower in 2020.

In light of CPS guidance and court closures, it seems likely that a significant number of these could have been out of court disposals.

If this is the case, and if policing has been able to effectively uplift the numbers of out of court disposals used without adverse effects (for example on reoffending or victim satisfaction), the implications for the future delivery of swift justice are profound.

Clearly, policing and its partners will want to review how appropriate any significant increase in the use of out of court disposals has been – in a number of situations a prosecution will always remain the right court of action. Over the coming months it will be equally as important to evaluate the impact of any increased use on reoffending. Either way there will be important lessons to be learnt from the policing response to the pandemic to carry forward.

Crest is currently conducting a new research project that will support forces to investigate this.

We are asking: How did the criminal justice system fare in the face of a pandemic and what can we learn from the crisis? What legacy will Covid-19 leave?

If you are interested in contributing to the project, in particular in relation to the use of out of court disposals in response to the crisis, please get in touch – www.crestadvisory.com.

Ellie Covell is Strategy and Insight Manager at criminal justice consultancy Crest Advisory.